The Johanna was the first English East Indiaman to be wrecked on the South African coastline. She was an English East Indiaman of 550 tons, commanded by Captain Robert Brown.

The remarkable tale of the loss of the Joanna starts on the afternoon of 24 February 1681, when Joanna,, sailed from Downs in England, in the company of four other vessels- The Nathaniel, The Williamson, The Welfare and The Sampson. The fleet was bound for Surat and the Bay of Bengal to trade and as was the case for the three centuries of this trade between Europe and the East, these outward –bound East Indiamen carried specie- usually silver and in the case of the Joanna nearly 70 chests of cob coins and pieces of eight- non-ferrous metals such as lead and copper, and other trade goods available in Europe. These goods would be exchanged in India for valuable raw materials such as spices, timber and tin, as well as highly prized eastern manufactures, like porcelain and silk cloth, which were in great demand in Europe where nothing comparable was available.

Like her companions, the Joanna was named after the Johanna Islands in the Comores- was a small vessel of only 55 tons, although she carried 36 iron guns. She was launched in 1671 and was already a veteran of five successful voyages to the East.

Navigational Problems:

Navigational Problems:

Almost three months to the day after leaving England, the Joanna had reached the approximate position of 36degrees latitude, but foul weather and grey skies had prevented the captain and crew from making navigational observation for eight days and they had no accurate idea of where they were.

Dawn on Sunday 28 May again revealed grey skies, a strong north-westerly wind and heavy seas, but in the early hours of Monday morning the sea calmed and the crew hoped that they would see land once the sun rose. Based on his estimate of Joanna’s position, however, the captain believed that the ship was well south of any land and that it was pointless deploying leads men at this stage as the water would be far too deep to sound the bottom. Instead he instructed the helmsman to steer an easterly course and to maintain watch.

Dawn on Sunday 28 May again revealed grey skies, a strong north-westerly wind and heavy seas, but in the early hours of Monday morning the sea calmed and the crew hoped that they would see land once the sun rose. Based on his estimate of Joanna’s position, however, the captain believed that the ship was well south of any land and that it was pointless deploying leads men at this stage as the water would be far too deep to sound the bottom. Instead he instructed the helmsman to steer an easterly course and to maintain watch.

Captain’s error on that fatal night

Captain’s error on that fatal night

Half an hour before the end of the watch, one of the crew reported sighting land off the weather bow, towards the northwest, but although the other sailors gathered round. Straining to see through the gloom, the visibility was so poor that nothing could be seen. The captain was informed but told the crew not to worry as they were still too far southwards of 35 degrees latitude for land to be a threat.

Then, just after the bell had been rung for the next watch, and with only two hours before sunrise, the Joanna struck, very gently. The helm was immediately put over and the fore sails and sprit sails were loosed to try and get the ship off, but as she began to weather, she struck the bottom hard once again, breaking her tiller, and the wind drove her onto the rocks.

In the darkness, confusion reigned.

The pumps were manned, but water was rising rapidly in the hold, reaching the gundeck within minutes. When the seas began breaking over the decks, the masts were cut away in an effort to stabilise the vessel and keep her from keeling over and breaking up. At daybreak, the coast could be seen, a bay with a sandy beach and long stretches of rocky coastline on either side. The wreck of the Joanna was found to be lying helpless on a rocky reef, about three leagues offshore.

To the consternation of those aboard the Joanna, another ship, probably the Welfare, was seen in the distance, very close to the shore. As the crew of the Joanna watched, the vessel managed to claw itself clear of the rocks and sail away, unable to stop and render assistance.

Each man for himself now..

The dejected crew was cajoled into action by the captain and officers, and the two ships’ boats were launched. However, one look at the reefs between them and the shore convinced many of those aboard that the boats would not make it, so they constructed life rafts from the spare mastheads, on which 56 men reached the shore. The two boats also managed to reach the beach carrying the captain and 35 crewmen, but 25 men still remained aboard the wreck, which was now beginning to break up.Eighteen of these men reached the shore in safety in the next few hours on an assortment of wreckage and makeshift rafts, but six perished in the waves.

Overland to Cape Town

Later that day, survivors set out to walk to the Cape, carrying some food they had managed to collect on the beach after the wreck. After four days of walking and beginning to suffer the ordeal, they encountered a group of Khoi herders, who took them to the kraal of chief Klaas, the local representative of the Dutch authorities in the area. They were fed and cared for and provided with food and guides for the journey to Cape Town. Captain Brown, who had fallen ill and was too weak to walk any further, stayed behind as a guest of Klaas.

Governor Simon Van Der Stel

Governor Simon Van Der Stel

On June 18, ten days after the Joanna was lost, three weary sailors, followed by the rest of the crew, arrived at the Castle with the news of the wreck. The Governor, Simon van der Stel, immediately dispatched a wagon to fetch Brown and the shipwrecked seamen were again well looked after, the VOC officials at the Cape ensuring that they were comfortably lodged, clothed and provisioned until a passage home could be arranged.

–

SALVAGE Joanna’s Treasure

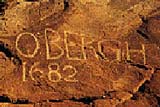

When Van der Stel learned that the Joanna was carrying a large cargo of specie, he sent a secret party headed by the Swedish explorer, Olaf Bergh, to the scene of the wreck to recover what had been washed ashore and salvage any specie they could from the wreck.

When Van der Stel learned that the Joanna was carrying a large cargo of specie, he sent a secret party headed by the Swedish explorer, Olaf Bergh, to the scene of the wreck to recover what had been washed ashore and salvage any specie they could from the wreck.

They reached the wreck site 22 days after the disaster and, scouting the beach found four bodies, which they buried. They also found 600 coins scattered among the rocks, the remains of a money chest and some other flotsam such as copper pipes and liquor, all of which were stored in a tent on the beach

–

Olaf Berg took control of the salvage operation

Olof Bergh, a Swede from Gothenburg, born in about 1643 into an aristocratic family, arrived in the Cape in 1676. Before his first journey along the West Coast he undertook a number of bartering trips to the Overberg and to salvage the English ship Joanna that had run aground at Danger Point.Bergh found that the wreck could be reached by boat in calm weather and asked the Governor to send a carpenter and a slave from the East, a pearl diver by the name of Pay Mina, from Cape Town to assist them.

Olof Bergh, a Swede from Gothenburg, born in about 1643 into an aristocratic family, arrived in the Cape in 1676. Before his first journey along the West Coast he undertook a number of bartering trips to the Overberg and to salvage the English ship Joanna that had run aground at Danger Point.Bergh found that the wreck could be reached by boat in calm weather and asked the Governor to send a carpenter and a slave from the East, a pearl diver by the name of Pay Mina, from Cape Town to assist them.

–

JOANNA SHIPWRECK – SOUTH AFRICA – 1682 – MEXICO CITY MINT – 8 REALES

A small VOC yacht which served the Cape, the Jupiter, was also sent to help recover as much of Joanna’s equipment as possible, Finally three months later, leaving “in the name of God”

A small VOC yacht which served the Cape, the Jupiter, was also sent to help recover as much of Joanna’s equipment as possible, Finally three months later, leaving “in the name of God”

Bergh arrived back at the Castle on 13 September 1682 with two wagon loads of salvaged items, including the ship’s bell. He gratefully received a prize included a specie of 28 102 gulden.

The Johanna lay untouched and lost for 300 years,

The Johanna lay untouched and lost for 300 years,

until Charlie Shapiro and his group, which consisted of Gavin Clackworthy, Bert Kutzer, Tommy Botha, Andre Hartman and Erik Lombard, discovered her remains in 1982.

Quoin Point, a shipwreck graveyard

The site was located on the outer reefs of “Die Dam” east of Quoin Point. Most of the site lay under sand, and a prop-wash machine was purchased to excavate this shallow site. Over 23,000 cob coins were recovered as well as a few hundred kilograms of silver bullion in the form of disc ingots. 44 Iron cannon were located on the site, but more are rumoured to have been seen on shore by older fishermen.

Earliest recorded active salvage operation on a Southern African coast

Earliest recorded active salvage operation on a Southern African coast

The extreme diving conditions these modern divers experienced on the site make the accomplishments of

Bergh and Pay Mina, the pearl diver, in what was recorded one of the earliest recorded active salvage operations in South Africa-a mere thirty years after the establishment of permanent Dutch settlement at the Cape, truly astonishing.

Shipwreck Museum

The shipwreck museum in Bredasdorp depicts the sad and heroic tales of hopes and lives lost on the treacherous Agulhas coast around the most Southern Tip of Africa. Visitors welcome.