A Dyer Island Conservation Study in Gansbaai Sheds Light on White Shark Hunting Behaviour

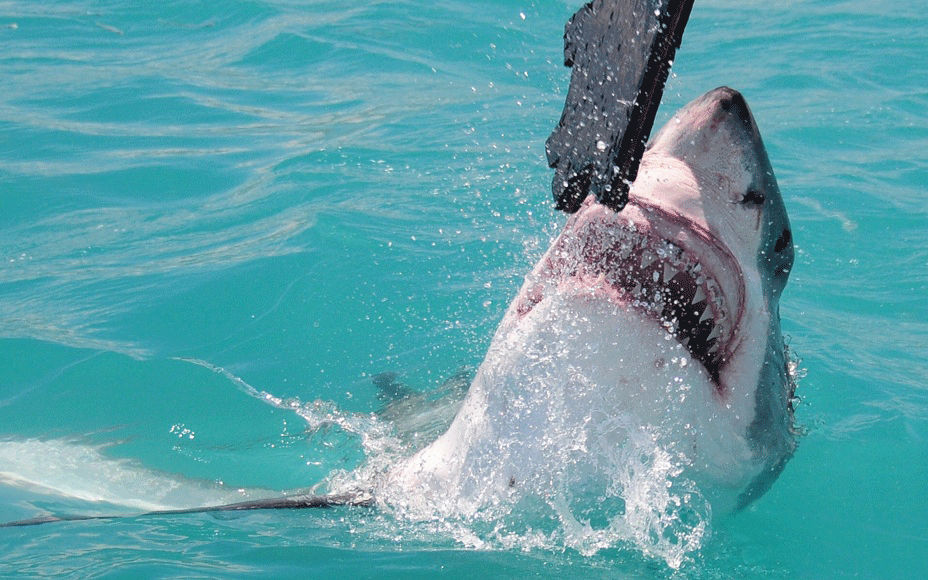

When we think of great white hunting behaviours, the iconic image that comes to mind is that of a white shark breaching from the water, a seal clamped helplessly in its jaws. White Sharks represent the archetypal ambush hunter to many of us, suggesting there may be more to their hunting techniques than initially meets the eye.

The research took place in Gansbaai, well known as the white-shark-diving capital of the world, and with one of the highest known densities of the species.

Great White Sharks use varied hunting methods

According to Alison Towner, a marine biologist who participated in the study, predators typically employ one of two hunting methods. They either lie in wait for prey to come to them (in the manner of crocodiles), or actively patrol for their food (like cheetahs). The results of the Gansbaai research study show that great whites may do both, switching between the two hunting behaviours depending on a series of external factors, including the time of day, the activities of local shark-diving boats, and the gender of the shark itself.

Males and females differed in their habitat use, with females using habitats closer to the bay in addition to Dyer Island and Geyser Rock, while males spent more time directly off Dyer Island

The findings also suggest that specific sharks may have their own preferences when it comes to hunting techniques, with individuals using the same tactics over and over again. This groundbreaking discovery is a first, confirming the status of the great white as one of the ocean’s most versatile predators. The research also hints that human activity may have a greater impact on the sharks than previously understood.

Wilfred Chivell, Dyer Island Conservation Trust founder who undertook the research, comments that the research “shows [that the sharks] use a more costly swimming mode around cage-diving boats, yet after diving activities cease for the day, the sharks resumed their natural hunting state whilst in the area.” It is not yet clear why the boats affect the sharks’ behaviour, whether it’s related to the fish oil they use to attract the sharks, or whether the boats’ presence itself is enough to affect the relationship between shark and seal.

Wilfred Chivell, Dyer Island Conservation Trust founder who undertook the research, comments that the research “shows [that the sharks] use a more costly swimming mode around cage-diving boats, yet after diving activities cease for the day, the sharks resumed their natural hunting state whilst in the area.” It is not yet clear why the boats affect the sharks’ behaviour, whether it’s related to the fish oil they use to attract the sharks, or whether the boats’ presence itself is enough to affect the relationship between shark and seal.

“It is known that chumming does not impact the migratory behaviour of white sharks, but less is known about the short-term behaviour when they visit regions along our coast. Studies are often limited to observations from anchored boats. This is [therefore, one of the most comprehensive studies on the natural behaviour of white sharks in Gansbaai.”

Dyer Island’s Vulnerable Marine Eco System

Understanding more about the area’s sharks is important because, as Towner points out, “[their] behaviour ultimately creates different pressures on other trophic levels, which is of particular concern in a complex and vulnerable marine system such as Dyer Island.”

In other words, as the region’s key apex predator, changes in the white sharks’ hunting behaviour have the power to affect other species further down the food chain and ultimately to impact the balance of the ecosystem as a whole. It’s hoped that the results of the recent study will help inform the ongoing protection not only of the sharks themselves, but also of the other species that share their home.